What are complex numbers? What does “i” mean, anyway? How can a number be “imaginary“? What does it mean to multiply “i” exactly “i” times? Why is math hard?

For me, math is difficult because it’s interesting. I learn things from equations that aren’t obvious when I think about the world using words and images. Some things can’t be put into words. Some things can’t be pictured.

It’s true.

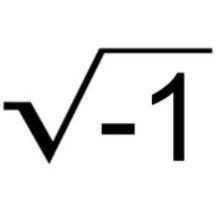

What makes ![]() interesting is the four real numbers it generates. (The numbers are +.2078… , -.2078… , +4.8104… , and -4.8104… .)

interesting is the four real numbers it generates. (The numbers are +.2078… , -.2078… , +4.8104… , and -4.8104… .)

Can anyone give a geometric reason why an imaginary number raised to the power of an imaginary number generates four real numbers and no imaginary ones?

What does ![]() even mean? Is there anyone who can visualize a reason why the answers make sense? Are all the answers even correct? Or is only one correct, as any calculator that can do the calculation will tell?

even mean? Is there anyone who can visualize a reason why the answers make sense? Are all the answers even correct? Or is only one correct, as any calculator that can do the calculation will tell?

Abstract math that hides no model that anyone can visualize makes results startling, even unnerving. It’s a lot like the quantum mechanics of entanglement or the physical meaning of gravity. They can be mathematically described and their effects accurately predicted, but no one can explain why.

Mathematics alone can sometimes describe (or at least approximate) realities of the universe and how it seems to work, but as often as not when humans dive deep into the abyss of ultimate knowledge, math is unable to provide a picture that anyone can understand.

How can that be? Things seem to happen that cannot be thought about except by playing around with numbers and being taken by surprise. Intuition is difficult, if not impossible.

Here is the solution of ![]() . Perhaps clues exist in the math that I’ve overlooked. If a model exists in the mind of a reader somewhere, I hope they will share it with me.

. Perhaps clues exist in the math that I’ve overlooked. If a model exists in the mind of a reader somewhere, I hope they will share it with me.

(1) ![]() = cos (ln i) + i sin (ln i)

= cos (ln i) + i sin (ln i)

By definition: ![]() = i

= i

Also: ![]() = ln i

= ln i

Therefore: ln i = i ![]()

It should now be obvious to anyone who has taken a basic course in complex variables that multiplying i ![]() by i equals the exponent on e in line (1).

by i equals the exponent on e in line (1).

Right?

It’s a real number that returns a real result when used as the exponent of e and plugged into a calculator. The answer is completely abstract, though. We might learn more if we take a different path to the result.

By substitution into line (1): ![]() = cos (

= cos (![]() ) + i sin (

) + i sin (![]() )

)

By half angle formulas: ![]()

Convert 2nd term i to ![]() :

:

![]()

(2) Simplify the 2nd term: ![]()

Euler’s cosine identity is: cos θ = ![]()

Therefore: cos (iπ) = ![]()

(3) Simplifying: cos (iπ) = ![]()

Substitute line (3) into line (2) and simplify:

![]()

Now it’s just a matter of pulling out an old calculator and punching the keys.

![]() = .043214;

= .043214; ![]() = 23.140693.

= 23.140693.

I rounded off both numbers, because they seem to go on forever like π and “e”; they prolly are irrational, because they don’t seem able to be formed from ratios of whole numbers. [In fact, they are transcendental numbers, because they transcend algebra. In addition to being irrational, they are not roots of any finite degree polynomial with rational coefficients. Take my word.] Using these numbers will enable anyone to compute ![]() who has a simple calculator with a square root key.

who has a simple calculator with a square root key.

When square roots are calculated the answers can be positive or negative. Two negatives make a positive, right? So do two positives. So doing the math gives four numbers. See if your numbers match mine: .2078… , -.2078… , 4.1084… , and -4.1084… .

I don’t know why. The answers aren’t intuitive. Who would guess that imaginary numbers raised to powers of imaginary numbers yield real numbers? — not a solitary number like anyone might expect, but four. Pick one. In nature a unique answer can be arbitrary — determined by chance, most likely.

In this case, no.

It feels to me like the imaginary fairies flying around in complex space are destined to collapse onto the real number line for no good reason, except that the math says they must collapse (maybe from exhaustion?) in at least one of four places. Can anyone make sense of it?

The ln i is well known. It is — ![]() — which equals (1.57078… i ). The ln of —

— which equals (1.57078… i ). The ln of — ![]() — can be rewritten by the rules of logarithms as i ln i, which is i times (1.57078…i ), which equals -1.57078… (a real number). Right? The ln of the correct answer must equal this number. Only one of the four results listed above has the right ln value: .2078… .

— can be rewritten by the rules of logarithms as i ln i, which is i times (1.57078…i ), which equals -1.57078… (a real number). Right? The ln of the correct answer must equal this number. Only one of the four results listed above has the right ln value: .2078… .

It seems odd that a set of equations I know to be sound should return a set of results from which only one can be validated by back-checking. Maybe there is something esoteric and arcane in the mathematics of logarithms that I missed during my education along the way.

Then again square roots can be messy; there are two square roots in the final equation, each of which can be evaluated as positive or negative. Together they produce four possible answers, but just one result seems to be the right one.

Adding the four numbers is kind of interesting. They sum to zero. That is so like the way the universe seems to work, isn’t it? When everything is added up, physicists like Stephen Hawking claim, there’s really nothing here. Everything is imaginary. Some philosophers agree: everything that is real is at its core imaginary.

Are there clues in the pictures and models of complex number space that would ever make anyone think? Sure, I totally get it. Yeah, I’ve got this. Real numbers cascading out of imaginary powers of imaginary numbers make perfect sense — like snowflakes falling from a dark sky.

A mathematician told me, Rotating and scaling is all it is. The base must be the imaginary ”i” alone; ”i” is the key that unlocks everything. The power of the key can be any imaginary number at all; ”i” is why the result of every imaginary power of ”i” becomes real.

The explanation calms me; but it seems somehow incomplete; it’s missing something; in my gut I feel like it can’t be entirely right, though it purports to persuade what the math insists is truth.

Believe, for now at least, and move on.

Billy Lee

. The point is shown at .2078… on the

. The point is shown at .2078… on the